Did the great Gabriel Garcia Marquez ever write a mystery novel? Sort off, though of course, being Marquez, he wrote a story that's rich and strange and that does some peculiar things with the mystery form. It's his short but remarkable book Chronicle of a Death Foretold, and I wrote a piece about it, looking at it as crime fiction, for the Criminal Element website.

You can check the piece out here: Chronicle of a Death Foretold.

Sunday, December 21, 2014

Thursday, December 11, 2014

Guest Blog: Dana King on How a Character Can Evolve

By Dana King

I want to start by thanking Scott for this opportunity to talk about my series protagonist, private investigator Nick Forte. Among the things Scott suggested I might write about was how Forte changes over time. This was in my wheelhouse, as he’s changed quite a bit over the course of the series. What’s interesting—to me, at least—is that it wasn’t planned.

First, it should be pointed out that, while I’m here today

to promote The Stuff That Dreams Are Made

Of, which is the second Forte story, there are two more on my hard drive

that have been ready for several years and will be released over the coming

months. He also has an important “guest starring” role in one of my Penns River

novels, Grind Joint. More people know

him as the badass in Grind Joint than

as someone who needs intervention to be saved in his original story, A Small Sacrifice. What happened to him?

Family issues and the relationships between parents and

children are a common thread in all the Forte books. A divorced father who adores

his daughter, Forte believes he can never be as good a father as one who lives

at home. This makes him prone to transferring his protective nature to some of

his clients, who tend to have a great deal of violence done to them, physical

and otherwise, often with few, if any, consequences. This is a problem for

Forte, who finds himself much more willing to meet violence with violence as

the series progresses, until he eventually crosses the line into what I think

of as prophylactic violence, violence as a preventive measure.

This was never the plan—I always thought of Forte as an Everyman with skills—even after the first four books were written. Then, preparing for his role in Grind Joint, I looked back and saw how he had become darker and less bothered by violence, both done to him and by him. This presented some delicious options to ponder. For instance, in Forte’s books, he has his own version of Spenser’s Hawk, named Goose, to fill what has been called by many as the “psycho sidekick” role. (I don’t think of Goose—or Hawk—as psychos, but that’s the term, and I can live with it. Mouse and Bubba Rogowski, now those are psychos.) Given Forte’s evolution—or devolution, depending on your point of view—the hero of the Nick Forte series is able to serve as the psycho sidekick when he travels to Penns River for Grind Joint, taking the case places his cousin, the cop, can’t or won’t go.

This change also allows the character to have more layers in

the upcoming fifth Forte story, tentatively titled Bad Samaritan, where Goose is more engaged in reining in Forte than

the other way around. The series will have flipped from a hero with a violent

sidekick to a violent hero with the same sidekick trying to act as a governor.

It’s Goose who remains the constant.

Bio Info:

Dana King’s new release, The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of,

follows the Shamus-nominated A Small Sacrifice, featuring Chicago private

investigator Nick Forte. He also writes a series of police procedurals set in

the economically depressed Western Pennsylvania town of Penns River.

Classically trained, he has worked as a free-lance musician, public school

teacher, computer network engineer, software sales consultant, and systems

administrator. He lives in Maryland with his wife, Corky, and daughter, Rachel.

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

The Mind is a Razor Blade

Kudos to Max Booth. In The Mind is a Razor Blade, his second novel, he could have written a follow up to his debut novel Toxicity by doing more of what he did so well in the first book. Toxicity is a dark but raucously funny crime novel with three or four intersecting plot lines, and as its story jumps from character to character, it gets inside the heads of several people. It is told in the third person throughout. By contrast, The Mind is a Razor Blade is a first person narrative, a novel that locks you from its opening line inside the brain of one man. That he's a man utterly confused, lost, is clear from the get-go. He's disoriented because of memory loss, and since everything in the book is told through his perspective, we're as limited in our understanding of the events happening to him as he is. We look for clues and search for meaning as he does; we try to make sense of the world he inhabits. It's a violent nightmare world that he moves through - a world Hieronymus Bosch would be proud of - and the whirlwind of bizarre incidents has some particular significance for him. What is that significance, though? That's the question the narrator and the reader need answered.

The trope of the amnesiac struggling to find out who he is and why he's so capable of certain actions (killing, for example, like our guy in this book can do easily) is an old and familiar one. But Max Booth gives it fresh life. The Mind is a Razor Blade opens in media res, with the narrator coming to consciousness naked in the woods, lying in the mud, near a corpse marked with bullet holes. Within moments of realizing that he must've killed the dead man, the narrator shoots and kills a cop. All this while he's trying to get his most basic bearings about himself and why he is in such a tense predicament. In its immediacy and noirish mood, the feeling of a mind bursting awake but still befogged, this opening reminded me of the film Memento. But where the author takes his story from this dramatic start goes well beyond mere noir or any one specific genre. Our narrator, later called Bobby, is living in a world that's somewhat futuristic (in a post-industrial, anarchic, dystopian kind of way), but it's a world that also has soul-takers, demons, telekinesis, and spiders that live in people's necks. All sense of civil, organized society seems to have collapsed; every conceivable type of degenerate has full access to the streets. The police may exist, as the first scene showed, but chaos and violence predominate. Destruction, fear, and rottenness are everywhere. And over the entire insane spectacle hovers a chilling and mysterious word, carried by bums on cardboard signs, spoken by others to the narrator, a word that rings in our narrator's head - Conundrae. What is Conundrae? Who is Conundrae? And why do people refer to that name in tones of awe and terror, like the haunted people in a Lovecraft story whispering of the entity Chulthu?

In The Mind is a Razor Blade, Max Booth concocts a tale that is part crime story, part horror novel, part science fiction, part psychological thriller. He fuses these genres effortlessly into a coherent whole, an energetic and engaging work. The pace is brisk; horrific and revolting imagery mix with black humor and moments of surprising tenderness. And through it all, Booth takes a big risk. It's extraordinarily difficult to craft a novel that for most of its length provides few answers to the myriad questions posed. The reader really is in the dark as to the overall shape and meaning of what is happening, though the characters around the narrator all seem to have an inkling, or definite knowledge, of the general pattern. At times, you feel as frustrated as the bewildered protagonist. When will we get some clear answers? you wonder. Why do all those people know something, while I know virtually nothing? Is the narrator in a half-dead, half-alive state, a twilight state like the hanged man's in Ambrose Bierce's "Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge"? Or maybe he's merely getting closer to death and everything is happening in his mind like we saw happened to the woman Mary in the horror film classic Carnival of Souls. These were among my thoughts as I read, and to be honest, I don't think I've read such a sustained exercise in hallucinatory mysteriousness since reading Iain Banks' great book The Bridge. Razor Blade has a mood and feeling similar to that Scottish masterpiece. It is both visceral and intellectual, and you never get the sense that the author doesn't know where he's taking us. He is the true master of this universe. He's got the chops and the confidence to pull off the prolonged mysteriousness, and he trusts the reader to go along for the ride.

The Mind is a Razor Blade is not as reader friendly as Toxicity. It makes you work harder. Its payoff, ultimately, is bleaker. But what comes across is a person writing what he wants to write, what he feels he must write come hell or high water. And no matter how harsh things get in the world depicted, Booth never slips into despair. His narrator and the small band the narrator connects with have too much energy for that. Friendship is always possible, even love. A joke made in a difficult moment can work wonders. The struggle here, at bottom, is existential: the question is how to survive in a world so degraded, and how to retain some humanity. Fantastical as Booth's world is, it feels oddly enough like our own. All that pain, suffering, and torture, all that madness...How to deal with it? Through his narrator's actions, Booth ventures a tentative answer that seems to be akin to Italo Calvino's in Invisible Cities: "seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space."

Pick up The Mind is a Razor Blade here.

Sunday, October 12, 2014

Troubled Narrators, Troubled Times

What do these novels have in common?

Ernesto Sabato's The Tunnel

Albert Camus' The Stranger

James M. Cain's The Postman Always Rings Twice

Les Edgerton's The Rapist

They are all first person narratives told by men in prison for murder. Each book has a distinctly existential tone to it, and in each case, the narrator is self-serving and unreliable. Fascinating novels, each one, great examples of prison noir.

I wrote a piece about these books, focusing on Sabato's novel, for the Los Angeles Review of Books. You can read the piece in its entirety here:

TROUBLED NARRATORS, TROUBLED TIMES

Ernesto Sabato's The Tunnel

Albert Camus' The Stranger

James M. Cain's The Postman Always Rings Twice

Les Edgerton's The Rapist

They are all first person narratives told by men in prison for murder. Each book has a distinctly existential tone to it, and in each case, the narrator is self-serving and unreliable. Fascinating novels, each one, great examples of prison noir.

I wrote a piece about these books, focusing on Sabato's novel, for the Los Angeles Review of Books. You can read the piece in its entirety here:

TROUBLED NARRATORS, TROUBLED TIMES

Friday, October 10, 2014

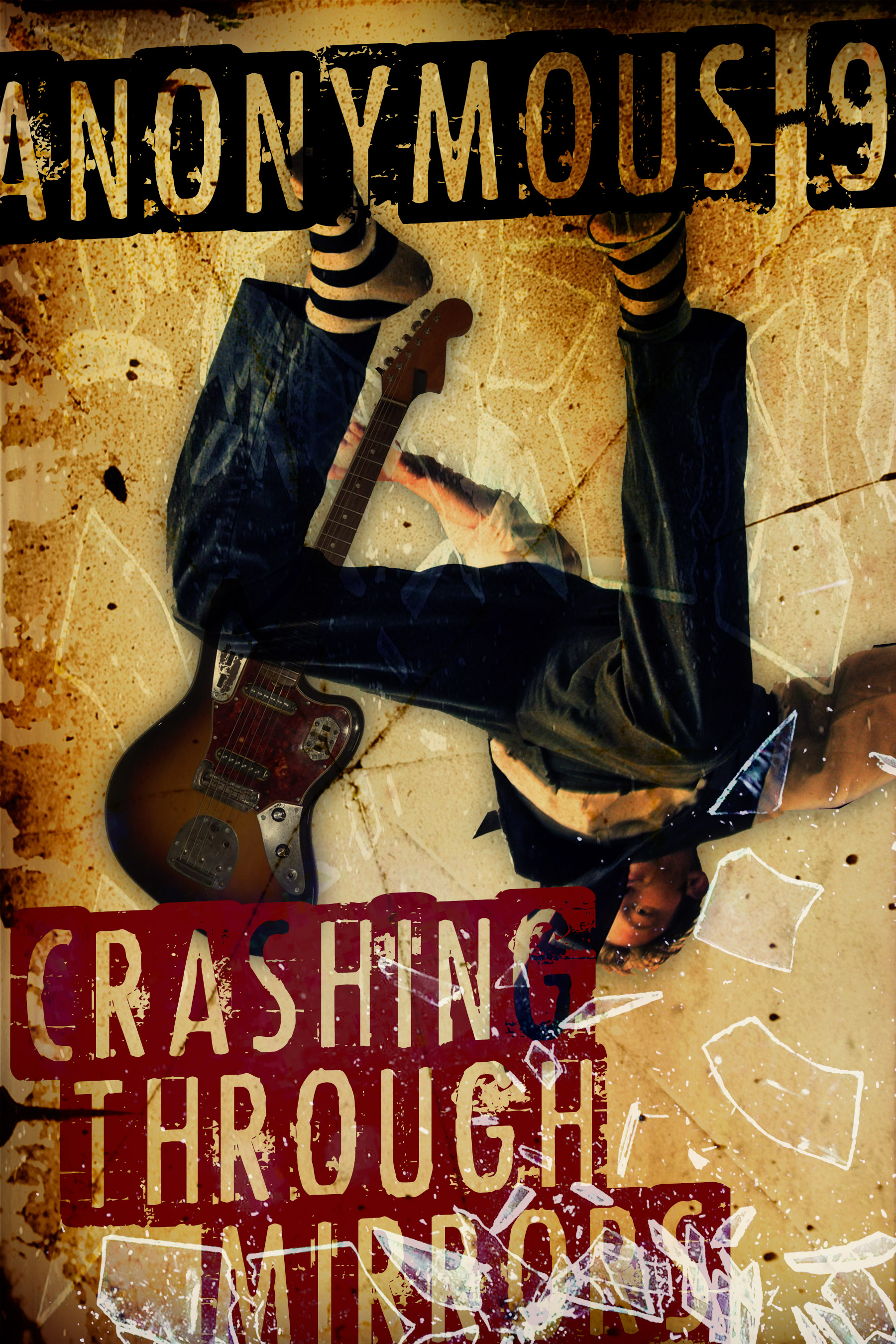

Review of Crashing Through Mirrors by Anonymous-9

Male rock stars are known for their sexual transgressions, so it's quite ironic when Bern Aldershot, Long Beach California guy made good, guitar man for the band that performed the great tune Crashing Through Mirrors years back, gets raped. It's ironic, but not funny. He is raped before dawn in a parking lot, in a vicious act involving wire cords, and like so many rape victims, he's loath to report the rape to the police. That is, until he realizes that he is one among a series of victims. In the months before his attack, two women were raped, and two months after his ordeal, a woman gets raped and killed. The man committing these crimes is escalating. Horrified and humiliated by his own violation, Bern didn't tell anyone about it, but after he sees a TV news story about the woman murdered by the serial rapist, he knows he has to tell the cops. He does, but in a twist that must confront many female victims of this particular crime, his story is doubted. His motives for why he took so long to come forward are doubted. He shows up at the police station unwashed and with booze on his breath, with his rock star reputation preceding him; you could say that in the cop's eyes he's the male equivalent of a "loose" woman. Who is going to believe his story? So he's forced to take action on his own, and what we then get in this novella by the fearless Anonymous-9 is something rather unusual - a male rape revenge story. The female rape revenge tale has become a familiar enough staple, but the different angle here adds a charge, a frisson. And when you throw into the mix, a teenage girl (named London) who Bern comes across and eventually befriends, his connection to her putting her at great risk from the rapist, you have all the ingredients in place for a suspenseful novella with characters you care about. You keep reading fast to the end.

Crashing Through Mirrors is the first thing I've read by Anonymous-9, the pen name of Elaine Ash. She writes the Hard Bite series about a paraplegic who kills hit-and-run drivers with the help from a monkey named Sid. That premise may sound farfetched, but if Crashing Through Mirrors is any indication, Anonymous-9 is one of those authors who can take the outre and make it plausible. Her prose is sharp and economical in the hardboiled manner, but it also has an oddly light touch. Bern can be self-deprecating in a way that is both humorous and endearing. And the author is not afraid, even in a novella, to take a brief detour that doesn't advance the plot per se but adds wonderful tension and flavoring: Bern and London have an encounter with a motorcycle gang that shows how celebrity, for all the annoyances it brings with paparazzi and such, can also be a saving grace. Tatty parts of Los Angeles and Long Beach are evoked well in this novella, and one gets the sense throughout that Anonymous-9 is quite familiar with Bern's world. She needs just a sentence or two to set a scene, create an atmosphere.

Crashing Through Mirrors is a swift read that you should pick up. It entertains. My only quibble, if I can call it that, is the slight annoyance I felt at its brevity. I could have spent more time with these characters. I'd like to know more about Bern, his brother, and Bern's music scene, about London and her life, and even the killer. Why exactly did he rape one man and three women? What's his deal? The guy's a rapist/killer bastard, okay, but the author has got the makings of a striking, monstrous villain here.

Grow this thing, Anonymous-9. Give us more.

Crashing Through Mirrors is available from Amazon.

Thursday, October 9, 2014

A New Review of Jungle Horses

Sometimes you get a review so lovely, you have to post it. Here's one I just received from the great crime writer Les Edgerton:

I'd like to recommend a fantastic book I just read, Scott Adlerberg's JUNGLE HORSES. Here's my review of it:

Every great once in awhile, as a writer, I come upon a book that serves as a wake-up call as to why I originally wanted to be a writer and reignites that original fever. The first books I read that excited me about literature were novels that created entirely new worlds out of whole cloth. The Jules Verne novels, the Edgar Rice Burroughs tales, the stories set in places like nowhere on earth. And then, as time went on and I became more and more inured into writing professionally, I kind of forgot that original excitement. Well, it was just reignited. I picked up a copy of Scott Adlerberg’s newest novel, JUNGLE HORSES, and instantly felt like I was 7 or 8 again, racing through 10,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA or TARZAN OF THE APES. I was immediately transported into a world that had never existed before and it was just plain exhilarating! This was a writer who was obviously the kid the English teacher back in the eighth grade singled out when she announced to the class that this kid had a wonderful imagination. Too often, as we get older and more jaded, we keep using the same old settings and same old plots and when you happen on a story like JUNGLE HORSES, it feels like it does when a Santa Ana comes down out of the mountains in L.A. and blows all the smog out to sea and the air gets crisp and clean and your lungs feel like new.

I’ll leave it to others to describe the plot, except to say that it involves a degenerate gambler, a weird sexual triad with one of the players impotent, and an island that I think broke off from the island of Dr. Moreau and drifted a few leagues away. And horses. It almost doesn’t matter what the plot is—it’s a dream and you enter into it immediately and willingly. Because of its atmospheric quality, it will be tempting to call it a work of noir, but it has a higher and reaches it—this is literature and literature of the highest quality.

I’ll leave the plot details to the cover copy, which describes it as:

Arthur lives a quiet life in London, wandering from the bar to the racetrack and back again. When his pension check dries up, Arthur decides to win it all back with one last big bet at the bookie. When that falls through, Arthur borrows money and repeats the process, until he's in too deep with a vicious gang of leg-breakers.

The plan to save his skin will take him far from his home, to a place where a very different breed of horse will change his life forever.

The plan to save his skin will take him far from his home, to a place where a very different breed of horse will change his life forever.

I have no idea why, but the entire time I was transported into Adlerberg’s tale, I kept thinking I was reading a story by William Goyen. I think it was the voice he employed.

I’m just thankful for coming upon a story that reminded me of why I wanted to be a writer. I feel like my own roots have been rejuvenated. It’s a wonderful thing to be reminded of the possibilities of story.

Pick up a copy--you'll be glad you did!

Blue skies,

Les

Saturday, September 27, 2014

DEADLY DEBUT: Murder New York Style

As a New Yorker, I spend so much time armchair traveling through crime fiction, reading stories and novels set in foreign countries - Britain, Sweden, Italy - or parts of the US where I don't live - Los Angeles, the South - that I sometimes forget what a great crime city my hometown is. Sounds strange, but it's true. When I'm looking for a mystery or a noir story to read, I think first of getting away to someplace unfamiliar, someplace that the story will allow me to explore through it. New York City I see every day, and I don't want to spend too much of my precious leisure time submerged in the familiar. Still, when it came to Deadly Debut, something about the New Yorker magazine styling of the cover caught my attention. And the cover announced, "Murder New York Style." Why not? I thought. Stay local for a change. Deadly Debut is a mystery anthology edited by Clare Toohey for the New York/ Tri State Chapter of SISTERS IN CRIME, and I have to say I'm glad I did pick it up.

The anthology contains seven stories written by women and for the most part centered around women. We get stories set in all five boroughs and one even set in Westchester. With each one, it's clear that the author knows her territory. Each presents a slice of New York you may feel you know but which in fact you haven't quite seen. No overly used spots or neighborhoods among these tales. This gives the whole collection a freshness that is welcome, and as I read, I experienced the pleasant sensation I get when reading fiction set, say, abroad. I felt, just a little bit, like I was exploring.

Elizabeth Zelvin's "Death Will Clean Your Closet," the first story, takes place in the old neighborhood of Yorkville, on the Upper East Side. It captures quite sardonically the preoccupations of a certain kind of cramped Manhattan apartment dweller. Closet space and the thinness of the walls can affect a New Yorker's life very much, and how well do you actually know your apparently innocuous neighbors? You pass them every day in the hall, and all you may know is that they like heavy metal and cook a lot with garlic. But if there's more to them than that? This was among my favorite stories in the collection.

"The Lie", by Anita Page, is a poignant memory piece set in 1949 on the Queens-Long Island border. It's a tale of sad violence that is also about the inevitable change that comes to the area where you grew up. It goes without saying that you can't go home again.

Terrie Farley Moran's "Strike Zone" takes you back to 1961 in the northern Bronx. It's a complex story told by an adolescent girl less interested in boys than in an author she discovers one summer - Edgar Allan Poe. She lives near the cottage Poe inhabited for years, and the master's tales of murder and obsession fascinate her. Not coincidentally, she has fantasies of killing a teenage boy who's always hounding her as only teenage boys can. But how can he not seem insignificant when the only boys who do interest her are Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, the historic year of their great home run race? Moran's prose is lucid and quick, and everything ends on an appropriately chilling, Poesque note.

Overall this is a strong collection, with good variety among the authorial voices, and I'd be remiss if I didn't mention that I also especially liked "Murder in the Aladdin's Cave", by Lina Zeldovich. The Aladdin's Cave is a go-go dancing club, the main character one of the dancers there. It's an unusual and evocative place to set a mystery, and the murder that occurs there is a variation on the locked room type, always fun. Zeldovich gives us a colorful cast of characters and suspects, and I had to wonder whether the hip-scarved sleuth Eve Gulnar has starred or will star in other adventures.

Deadly Debut: It's New York, it's crime, and it's entertaining. What more could you really want from a collection?

Tuesday, August 26, 2014

A Movie That Has Grown on Me

Bryant Park, where I do my film talks series each summer, asked me to write a few words about the last movie of the summer playing in the film festival there this year - The Shining. What can be said about this movie that hasn't been said, often nuttily, already.....other than, when I first saw it, on its very opening night in 1980, I wasn't thrilled with it. And yet, over the years, few movies have grown on me as much as Stanley Kubrick's movie has. I first saw it when I was seventeen years

old, on its opening day – May 23, 1980.

Never had I been as excited to see a film. I’d read and loved the novel by Stephen King,

which, to this day, I consider a horror masterpiece. Stanley Kubrick was already one of my

favorite directors: 2001: A Space Odyssey,

Barry Lyndon, and even A Clockwork Orange (which I saw on HBO)

were all movies I’d seen more than once.

When the news had come out that Kubrick was adapting King’s novel, I

could barely believe it. The very idea of Kubrick doing a horror film, my

favorite genre then, was thrilling, and that he would adapt my favorite horror

novel seemed like something I’d dreamt. Then to hear that none other than Jack

Nicholson would star in the lead role as Jack Torrance was the icing on the

cake. I knew, positively knew, this

would be a film I would see, consider great, and instantly rank among my all-time

favorites.

It didn’t quite happen that way. Kubrick’s film makes a number of key changes to King’s book, and when I first saw the movie, these alterations bothered me. I understood that film adaptations don’t have to follow their source material and sometimes improve upon their source material by making changes, but the book version of The Shining seemed so well-suited to be a movie, I wondered why Kubrick had changed it. Of course I also grasped that Kubrick was being himself, the inimitable and original Stanley K, and that he had chosen the book not to rehash King’s ideas of fear and horror but to develop his own.

In a nutshell, one could say that King’s book goes for horror that is psychological and visceral. The characters face both emotional dread and physical fright. And you like and care for these people, including, up to a point, the tormented Jack Torrance, who transforms from troubled but loving father to his wife and young son into homicidal raging monster of a father. It’s the primal quality of that transformation – father as protector into father as monstrous destroyer – that carries power in the book, and as the tension in the book grows, you are right there with the characters, feeling, at different times, the conflicting emotions of each of them.

Kubrick, on the other hand, keeps you at a distance. He cast Shelly Duval as Jack’s wife Wendy in part because, superb actress though she is, she has an odd, eccentric quality that doesn’t make her “audience-friendly”. Even Danny Lloyd, who plays their son Danny, has an aloof manner. The film unfolds in a way that is more like a slow burn than a traditional horror thriller, and this rhythm, even as a Kubrick fan, annoyed me just a bit. Added to which was the film’s ending, the last scene, something not in the book. While King resolves the novel with safety and closure, the horror finished (though there will be mental scars), Kubrick’s movie ends on an enigmatic note that left me frustrated. It didn’t seem necessary. Why couldn’t Kubrick, for once, just do things in a straightforward way? I asked myself. He had great horror material yet he directed it to create conundrum upon conundrum, going for creepiness more than real horror. I’d enjoyed the sardonic notes in the film – vintage Kubrick (and Nicholson) – and liked very much the last forty five minutes, when Nicholson is in full psycho mode pursuing Danny and Wendy, but the lead up to that part and its aftermath left me feeling disappointed. Still, I couldn’t let it go at that. This was a Stanley Kubrick film and nobody ever said Kubrick’s films are easy. You have to wrestle with them. You have to see them two or three times to do them justice. As I was leaving the theater, mulling over the film, I was certain I’d be seeing it again.

And I have. Many times since then, with an appreciation that grew and grew until now I see it as one of the great horror films. It does indeed build gradually, emphasizing eeriness and disorientation over shocks. It has an unnerving mood like no other film. True, you don’t get as emotionally attached to the characters as you do to King’s, but you watch with mounting dread as this small family unit, in chilling increments, implodes. There has never been a more disturbing portrayal of a writer blocked than Jack Nicholson in this movie, and the scene where Wendy discovers what he has been writing for weeks and weeks instead of his supposed novel is a definite classic. As with all Kubrick films, the music is effective - dissonant, jarring - and the famous Kubrick tracking shots make the Overlook Hotel seem at once huge and claustrophobic. By the time Nicholson’s character loses it and starts wielding an axe to kill his wife and son, you are mesmerized and on edge. The suspense of the last 45 minutes gets your pulse racing. You may sweat, but you also feel cold. You feel as if you’re trapped with Danny and Wendy in the snowbound hotel. And the riddles Kubrick poses, the multiple interpretations possible to explain everything that occurred? Now, to me, these only make the film seem richer – one reason I can see it over and over.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)